The Southern Highlands of New South Wales are unique in place and architecture. At Architecture Republic, we are passionate about this beautiful region. There is something about its layered vibrancy, its hillsides, its icy winds. It is impossible to describe the built environment of the Highlands in one architectural style. There is a diverse range because of our local climate, geography and history. In fact, it is the robust variety of size, age and styles all colliding that makes the Southern Highlands unique. The thing I love the most about our region is the variety. Walking down one street, you will see large, small, old and new. There is no one ‘neighbourhood character’ because every home is different. This vibrant layering of architecture is special and unique.

Today, we’re diving in. Let’s look at the colonial past and the contemporary present. Why certain architectural styles are common locally and their significance. We will also look at why understanding and preserving the area’s architectural heritage is crucial.

Early Architecture in the Southern Highlands

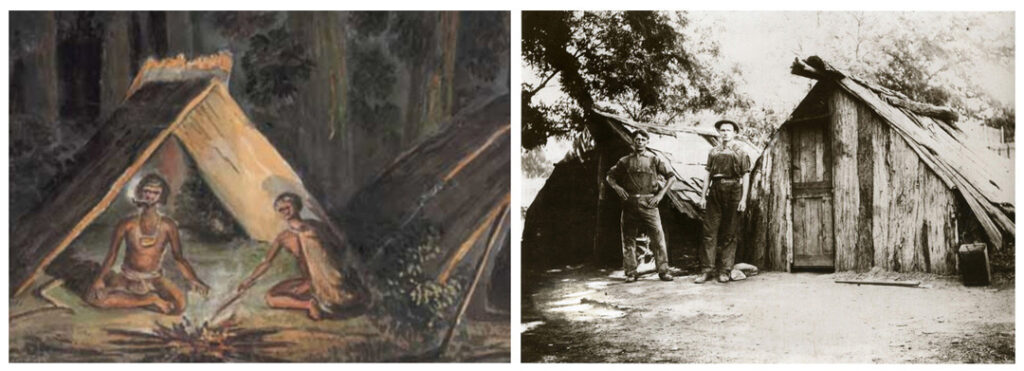

We are living on Gundungurra land. The words ‘Bowral’ (Bowrell), ‘Berrima’, ‘Mittagong’ (Nittigong) and even ‘Wingecarribee’ (Winge Karrabee) are all from the Gundungurra language. Early accounts of the Gundungurra people describe them as tall and strong with animal skin coats reaching their heels. They slept under “hut structures with jointed bark roofs”. This was a style that was probably copied by the early European colonists. In fact, Jemmy Moss (the namesake for the town of Moss Vale) is described as living in a bark hut throughout his life. Unfortunately, none of these bark-based buildings survive. The technique, however, did continue into the 1930’s (see photo below). Despite viruses, massacres and displacement, many Gundungurra people still live here. You can learn more at the Illawarra Local Aboriginal Land Council: https://ilalc.org.au/

R: Almost identical bark huts in Berrima (1930’s) – Berrima Historical Society

Georgian Architecture in Berrima

One of the oldest surviving buildings of the Southern Highlands is Oldbury Farm in Sutton Forest. (It is second only to the illusive ‘Browley’, a cottage built on the same road in 1825). Olbury is a Colonial Georgian house in the English style. It was built for James and Charlotte Atkinson between 1822 and completed in 1828. The house is a direct transplant, architecturally speaking, from England. It features heavy masonry, small windows and an entry porch instead of a veranda. We can see similar features on the Briar’s Inn in Burradoo. Briar’s was built on the Bong Bong Common in 1845 and later relocated up out of the flood zone. Ironically, Bong Bong means ‘river that loses itself in a swamp’ in the Gundungurra language. They probably should have asked before building there.

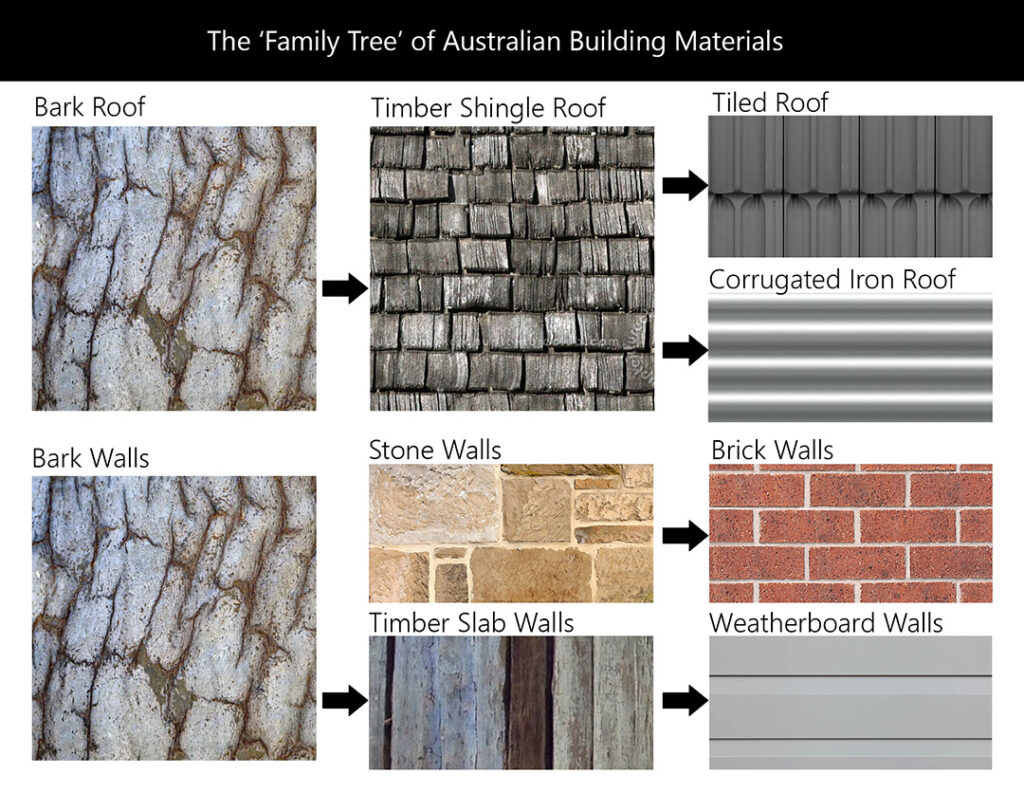

Over time the early bark huts made way for timber or stone cottages. Bark roofs were removed and replaced with wooden shingles. These were later roofed over with corrugated iron. We can construct an entire ‘family tree’ of Australian building materials over time. As industry (like Brickworks in Bowral and the Ironworks in Mittagong) took over, so did these more processed building products. Today, there are so many innovative options available, it would be impossible to list them all.

Surveyor Sir Thomas Mitchell gazetted the town of Berrima in 1830. This sidestepped the flooding issue in Bong Bong and the older town was left to decay. In Berrima we see a wealth of surviving buildings from this early period. In fact, we regularly describe Berrima as the only intact Georgian village on the Australian mainland. The railway bypassing the town in 1867 effectively froze its streetscape in time. All new local development centred on the railway station towns instead. The Georgian buildings in Berrima are famous for their symmetrical facades, balanced proportions and gable roofs. Here we can see surviving slab huts, stone cottages and early architectural adaptations to our local climate. A lot of them look like Oldbury, but with verandas and larger windows. Today, Berrima features 16 state heritage and 55 local heritage items. Most of these are clustered around Jellore St, Market Pl and Wiltshire St.

Victorian Architecture in Bowral

Victorian development focussed on the towns with railway stations (Mittagong, Moss Vale and Bowral). In this period, we see photos with a mix of the Berrima-style Georgian architecture and the later Victorian style. The railway (and the skills and materials it brought) made more ornate, larger buildings possible. Over time, many of the older ‘Berrima style’ buildings were torn down, not valued because of their ‘rough and ready’ construction.

In New South Wales, we usually associate Victorian architecture with terraces. In the Southern Highlands, however, we don’t see many examples of terrace homes. This is because during this era, Bowral and its surrounding towns were primarily country escapes for the wealthy. The cooler climate was ideal for the Sydney gentry who wanted to avoid hot summer days. These people wanted sprawling rural estates, not (workers’) terraces. As such, terrace architecture is only a small part of the local character.

There are also relatively few civic buildings from the Victorian era here. Berrima’s civic buildings (courthouse, gaol, post office) fulfilled this role until they were eventually too small. They became too small after this period when population surged again with the arrival of cars.

Where our Victorian architecture really shines, is in large rural estates. Retford Park (1887) in Bowral and Bunya Hill (1870’s) in Sutton Forest are classic and famous examples. Here, we see ornate facades, intricate details and the best of 19th century architecture. There really isn’t a lot to say, these buildings are cool and we’re lucky to have so many.

The Southern Highlands, Canberra and Alf Stephens and Sons

The Federation and Arts and Crafts styles both emerged at the turn of the 20th century. So did the Hume Highway (the Great South Road). It is impossible to overstate the impact that easy and convenient car access had on the Southern Highlands. In this time, we see more population growth. (With more freeway updates, the growth of Sydney’s fringe and the Work from Home revolution, we will continue to see population growth). And more people means more buildings.

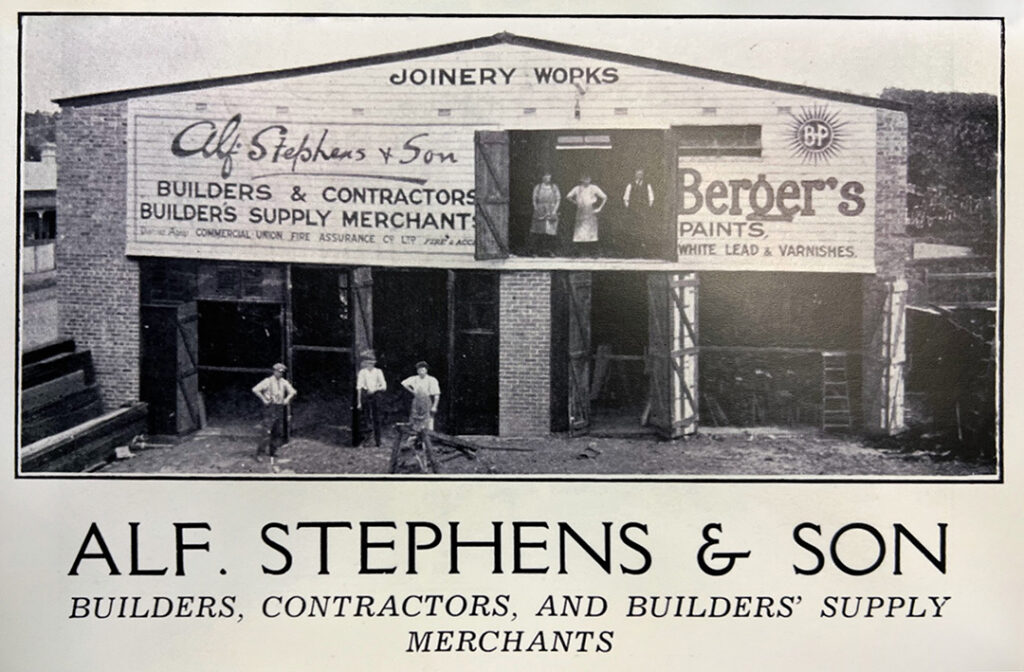

This is where we see Southern Highlands architecture really come into its own unique style. And that is, in no small part, due to the craftsmen in the image below:

Alf Stephens and Sons were local builders. They built an array of homes and public buildings in the Southern Highlands and (like us) in Canberra too. Their quintessential style was a mix of Arts and Crafts and Federation. These styles were both popular in the early 20th Century. Their residential work is instantly recognisable. Their homes are charming and character-filled. They often feature decorative brickwork, gabled roofs and timber detailing. They have wide verandas or porches, providing outdoor living spaces (a new phenomenon at the time). These homes also favoured a more horizontal orientation with a lower building profile. Something that was radically different to tall and narrow Victorian era homes. This ‘bungalow’ style is still popular today.

Here’s a list of their public buildings you may recognise. Alf Stephens built all of these in conjunction with various architects:

- Former Bowral Courthouse (1895)

- Superintendent’s residence, Berrima Gaol (1897)

- The Empire Picture Theatre, Bowral (1914)

- The Blue Illusion Shopfront (Formerly Shell Garage), Bong Bong St Bowral (1910’s)

- Bowral Golf Club House (1919)

- Ranalegh Hotel, Robertson (1924)

- St John’s Church, Moss Vale (1930)

- Hospital Buildings, Bowral (1933)

- Dormie Guest House in Moss Vale (1934)

- Canberra Girls Grammar School (1930-1940’s)

- Canberra Fire Station, Manuka (1938)

- Houses in Kingston, Griffith, Ainslie, Deakin, Reid and Yarralumla, Canberra (1930’s)

The similarities between ‘old’ Canberra and ‘old’ Bowral are striking. The first time we visited Bowral I remember Tristan saying “this is all very Ainslie”. It took us a while to figure out that Alf Stephens and Sons was why. This is the period where we start to see architectural elements that we still value today. We see verandas, familiar materials and even wider layouts with ‘plan sprawl’. These things were defined during the Federation and Arts and Crafts architectural movements. These homes are still popular and emulated today. The unique style of Alf Stephens and Sons has slowly become a timeless classic. With the right sympathetic alterations, these homes are as fantastic today as the day they were built.

Modern and Contemporary Architecture

The past 80 years have continued to see the Southern Highlands grow and build. The Cliff House, also known as The Seidler House, is a stunning example of modern architecture in our region.

The famous Harry Seidler designed The Cliff House late in his career. It is, possibly, his best project. This home showcases the principles of modernist architecture through its dynamic lines and a minimalist finish. It uses innovative structural solutions in the roof to reflect the curves of the Joadja landscape. It also features large glass windows and sliding doors so that the roof seems to float. This home understands the hillsides, the cliffs. Its smooth finishes contrast beautifully with the texture of the landscape around it.

The Cliff House is a brilliant example of midcentury and contemporary architecture. It is of its place, reflecting the landscape in its forms. Sadly, current council policies discourage buildings like this. Town planning is geared towards approving cheap mass-market homes that do not respond to site, climate or architectural context. What we tend to see is brick rectangles, focussed on privacy and large footprints. What does manage to get through, becomes a fantastic addition to our local architectural character. We do what we can.

Protecting Heritage Architecture in the Highlands

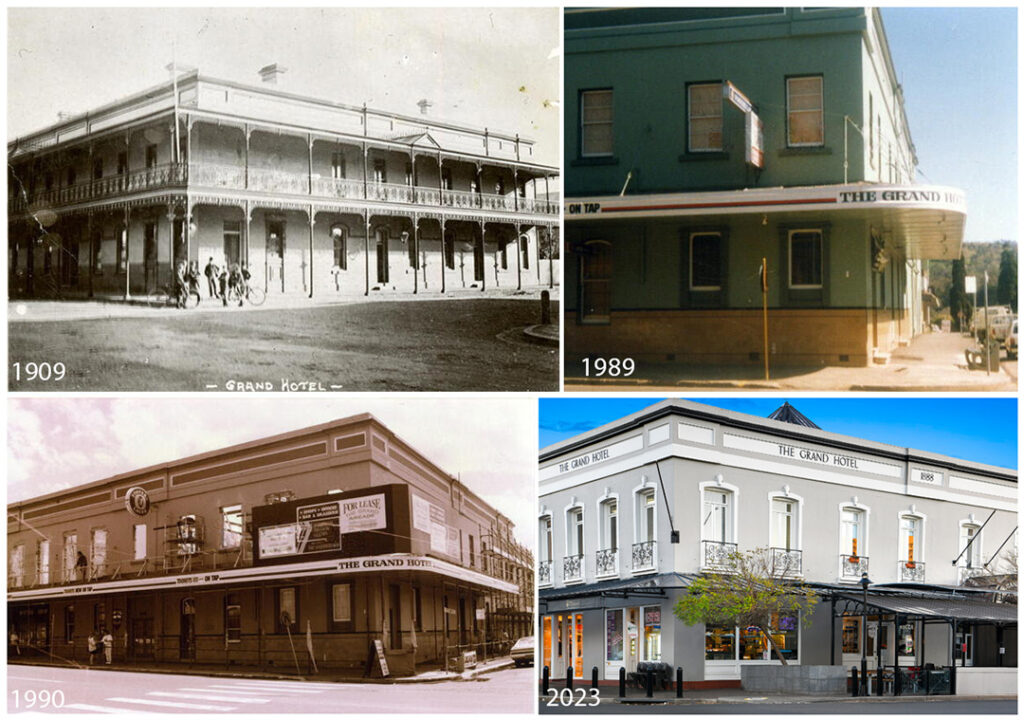

The history of architecture in the Southern Highlands wouldn’t be complete without a quick discussion of what we have lost. In particular, Council (and its precursors) committed the crime of mandating the removal of beautiful wrought-iron Victorian and timber Federation verandas off main street facades in the 1960’s.

This moronic initiative aimed to address concerns related to pedestrian and vehicular congestion. The goal was to ensure better traffic visibility and reduce potential hazards. This, along with the “modernisation” of the ground floor facades disguises the heritage of many local buildings. Would you have guessed the building above was old, if you only looked at the downstairs?

Particular victims included Argyle Street in Moss Vale and Bowral Road and the Old Hume Highway in Mittagong. Sadly, our Council wasn’t the only perpetrator of these ‘modernisation’ practices. The idea was widespread across New South Wales. We can see that the Snowy Monaro region (particularly the town of Cooma) suffered the same fate. Braidwood, on the other hand, survived with its beautiful facades intact. It’s heartbreaking to know that Moss Vale and Mittagong might have resembled Wallace Street in Braidwood, if not for this policy.

Braidwood and Berrima are prime examples of the benefits that came from neglect in a time where heritage architecture was not valued or appreciated. Today, we can do better. It is critical to understand our history, not just tolerate it. When we can read the layers of change and renovation, we can see what was built when. This means we can alter our buildings with sympathy instead of destructively. Modernisation can still happen without damaging our past.

Building and Renovating in the Southern Highlands: An Opportunity for Timeless Design

It is important to understand and preserve our local architectural heritage. We can also use this knowledge to inform our contemporary designs. You do not need to copy Oldbury to build ‘Southern Highlands Architecture’. We have so many other incredible precedents to use as inspiration. By maintaining the wide range of characters and styles of our region, we ensure that all types of heritage is valued and understood. One of the best things about this region is it’s lack of ‘neighbourhood character’. Every home has its own history and walking along almost any street will reveal an incredible range of heritage and contemporary styles.

As residential architects in the Southern Highlands, we are proud to be part of this rich and vibrant architectural landscape. Our goal is to continue to contribute to the region’s built environment, while preserving its unique heritage and diversity.

A big thank you to the ‘Local Studies Collection’ at Wingecarribee Public Library, Bowral for their incredible range of local history resources.